📂 Common File Formats

Not all file formats are created equal. The one you choose determines how much data Spark reads from disk, how tightly it compresses, and how fast your queries run. A bad choice here can quietly cost you 10x in query time and storage.

The Core Idea: How Data is Laid Out on Disk

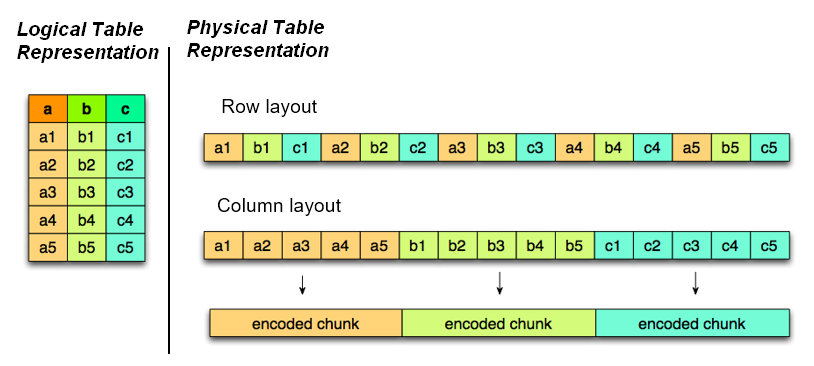

Every file format answers one fundamental question differently: do you store data row by row, or column by column?

Row format = one full record written together. To read column 5, you must scan all columns 1–100 for every row.

Columnar format = all values for column 5 stored together. To read column 5, Spark skips all other columns entirely.

This layout difference is the root cause of every performance gap between formats.

Row format saves rows line by line (like a .csv), while columnar format saves each column as its own separate block. When your query only touches 3 of 100 columns, columnar format does 97% less I/O (skips 97 columns entirely. Yes, its a simplification. In reality the saving depends on the actual byte size of each column).

Imagine you have a table with 6 rows and 4 columns — user_id, country, amount, timestamp.

Row format stores it like this on disk:

[u001, India, 500, 2024-01-01] → [u002, India, 230, 2024-01-02] → [u003, India, 890, 2024-01-03]

[u004, Germany, 120, 2024-01-04] → [u005, India, 670, 2024-01-05] → [u006, United States, 340, 2024-01-06]

Every row is written together. To get just the amount column, Spark must read all 4 columns across all 6 rows — including user_id, country, and timestamp that you don't need.

Columnar format stores it like this:

user_id → [u001, u002, u003, u004, u005, u006]

country → [India, India, India, Germany, India, US]

amount → [500, 230, 890, 120, 670, 340]

timestamp→ [2024-01-01, 2024-01-02, 2024-01-03, 2024-01-04, 2024-01-05, 2024-01-06]

Each column lives in its own block. A query on amount only reads that one block — the other 3 columns are never touched.

Run-Length Encoding (RLE). Because all values for a column are stored together, repeated values compress extremely well. The

countrycolumn above hasIndiaappearing 3 times. Therefore, instead of storing it 3 times, columnar formats encode it asIndia × 3. The more repetition in your data (status fields, country codes, boolean flags), the more aggressively it compresses. This is why columnar formats achieve 80–95% size reduction over raw CSV. This is something row formats simply can't match, since similar values are scattered across different rows rather than grouped together.

Here's a neat representation. Source

Why It Matters in Spark

Spark's execution model is heavily I/O-bound. Reading unnecessary data from disk wastes both time and money, especially on cloud storage (S3, GCS, ADLS) where you pay per byte scanned.

Columnar formats unlock two critical Spark optimizations:

- Predicate pushdown — Spark pushes filter conditions down to the file reader, which uses embedded statistics (min/max per column chunk) to skip entire row groups without reading them into memory

- Projection pushdown — Spark reads only the columns your query references, skipping all others at the I/O layer — before data even enters the JVM

Neither of these is possible with row-based formats. With Avro or CSV, Spark must deserialize the entire row to extract a single field.

CSV and JSON — The Plaintext Formats

CSV/JSON = human-readable, schema-less text formats. No compression, no statistics, no column skipping.

# Reading CSV — Spark must read every byte, infer types, parse strings

df = spark.read.csv("data.csv", header=True, inferSchema=True)

# Writing JSON — verbose, every field name repeated for every row

df.write.json("output/")

The problem: CSV stores every number as a string. A column of integers takes 5–10x more space than a binary integer. There are no embedded statistics, so Spark can't skip a single row during a filter and it reads everything.

When to use them anyway:

- Data exchange with external systems that can't speak binary formats

- Small files meant for human inspection

- Ingestion landing zones where downstream parsing flexibility matters

Avro — The Row Format Done Right

Avro = binary row-based format with embedded schema, designed for fast writes and schema evolution.

# Reading Avro in Spark

df = spark.read.format("avro").load("events/")

# Writing Avro

df.write.format("avro").save("output/events/")

Avro stores data row by row in a compact binary encoding. The schema (defined in JSON) is embedded in the file header — this makes Avro self-describing and enables schema evolution: you can add or remove fields without breaking downstream readers.

Where Avro shines — streaming ingestion:

Avro files are appendable. You can write row-by-row as events arrive — perfect for Kafka → Spark Streaming pipelines where data lands continuously. Parquet and ORC buffer rows in memory before flushing, which introduces latency and write overhead in streaming contexts.

The tradeoff: Because Avro is row-based, analytical queries that touch only a few columns must still deserialize full rows. On a 100-column table, that's 97 columns of wasted work per row read.

Parquet — Built for Analytics

Parquet = columnar binary format with embedded statistics, nested type support, and excellent compression. The default format for Spark.

# Parquet is Spark's default — just .parquet()

df.write.parquet("output/transactions/")

df = spark.read.parquet("output/transactions/")

# With compression (snappy is default, zstd for better ratio)

df.write.option("compression", "snappy").parquet("output/")

Parquet organizes data into row groups (default 128MB each). Within each row group, data is stored column by column. Each column chunk stores min/max statistics — so Spark can skip entire row groups during a filter without reading any data from them.

How Parquet's predicate pushdown works:

# Spark pushes this filter to the Parquet reader

df = spark.read.parquet("sales/") \

.filter("amount >= 10000")

# Parquet checks: "Does this row group's amount column have max < 10000?"

# If yes → entire row group (128MB) is skipped at I/O layer

# Result: Only a fraction of the file is read into memory

Parquet also supports nested structures (arrays, maps, structs) in columnar form using the Dremel encoding — no flattening required.

Compression benchmark (same 1TB CSV dataset):

- CSV: 1 TB

- Avro: ~240 GB (~76% smaller)

- Parquet: ~104 GB (~89.6% smaller)

- ORC: ~56 GB (~94.4% smaller)

ORC (Optimized Row Columnar Format)

ORC (Optimized Row Columnar) = columnar format with stripe-level indexes, bloom filters, and superior compression. Hive's native format.

# Reading and writing ORC in Spark

df = spark.read.orc("warehouse/")

df.write.orc("output/")

ORC organizes data into stripes (default 64MB). Each stripe contains an index with min/max statistics, and optionally bloom filters — hash-based structures that let Spark answer "does this stripe contain the value user_id = 'abc123'?" without reading the stripe.

Differences between Parquet & ORC:

| Parquet | ORC | |

|---|---|---|

| Layout unit | Row groups (128MB default) | Stripes (64MB default) |

| Statistics | Min/max per column chunk | Min/max + bloom filters per stripe |

| Compression | Snappy/ZSTD/Gzip | ZLIB/Snappy/LZO (ZLIB by default — better ratio) |

| Nested types | Native (Dremel encoding) | Supported but less flexible |

| Ecosystem | Spark, BigQuery, Snowflake, Athena | Hive, Presto, Trino, Spark |

| Default in | Spark, Delta Lake | Hive, Apache Hudi |

Why is Parquet more commonly used than ORC? ORC technically wins on compression ratio and has more advanced bloom filter support — but Parquet won the ecosystem war. Spark chose Parquet as its default format, and so did Delta Lake, Apache Iceberg, Google BigQuery, Snowflake, and AWS Athena. This means Parquet works natively across your entire modern data stack without any configuration. ORC remains the right choice if your stack is Hive or Trino-heavy, but for most teams building on Spark and cloud-native tools today, Parquet is simply where the tooling, community support, and integrations are strongest.

Predicate Pushdown in Practice

Here's what actually happens under the hood when Spark reads a Parquet/ORC file with a filter:

# Table: 500GB Parquet, 4000 row groups of 125MB each

transactions = spark.read.parquet("transactions/")

result = transactions.filter("region = 'IN' AND amount > 50000") \

.select("user_id", "amount", "timestamp")

# What Spark does:

# 1. PROJECTION PUSHDOWN → only reads 3 columns (user_id, amount, timestamp)

# Skips the other 97 columns entirely at I/O layer

# 2. PREDICATE PUSHDOWN → checks min/max stats for each row group:

# - Row group min_amount=100, max_amount=30000 → max < 50000 → SKIP

# - Row group min_amount=40000, max_amount=200000 → may contain matches → READ

# Result: Spark reads maybe 5% of the 500GB file

With row-based formats (CSV/Avro), step 1 and step 2 are both impossible. Spark needs to read 100% of the data into memory and then drop columns and filter rows.

Schema Evolution

What is schema evolution? Real pipelines change over time: new columns get added, old ones get dropped, types get updated. Schema evolution is a format's ability to handle these changes without breaking existing files or readers. Not all formats handle this equally well.

Here is how each format deals with schema changes:

Avro — schema evolution is a first-class feature. Adding a field with a default value, renaming via aliases, or removing optional fields all work without rewriting data.

Parquet — supports adding and removing columns. Adding a new column with nulls for old rows works seamlessly. Renaming or changing a column type requires rewriting the file.

ORC — similar to Parquet, supports adding columns but is less flexible for type changes.

CSV/JSON — no schema enforcement. Schema drift is silent and causes runtime failures downstream.

How Formats Interact with AQE and Partitioning

- Partition pruning skips entire folders. Predicate pushdown skips row groups inside the remaining files. Used together, they're multiplicative.

- AQE's broadcast join conversion benefits from Parquet/ORC because accurate row group statistics give AQE better runtime size estimates to decide whether to broadcast.

- Bucketed tables written as Parquet benefit from both column skipping and bucket co-location — the combination eliminates shuffle and minimizes I/O per executor.

Format Selection at a Glance

| CSV/JSON | Avro | Parquet | ORC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage type | Row (text) | Row (binary) | Columnar | Columnar |

| Compression | None | Moderate | High | Highest |

| Read speed (analytics) | Slowest | Slow | Fast | Fast |

| Write speed | Fast | Fastest | Moderate | Moderate |

| Predicate pushdown | No | No | Yes | Yes (+ bloom filters) |

| Schema evolution | No | Yes — best | Yes — partial | Yes — partial |

| Streaming writes | Yes | Yes — best | No | No |

| Nested types | No | Yes | Yes — native | Yes |

| Best ecosystem | Universal | Kafka/Flink | Spark/Delta/BigQuery | Hive/Trino/Presto |

When to Use What

Use CSV/JSON when:

- Sharing data with external systems or non-technical consumers

- Small, one-off exports for debugging or inspection

- Ingestion landing zones (convert to Parquet/ORC downstream)

Use Avro when:

- Writing streaming data to Kafka topics or Spark Streaming sinks

- Building event-driven pipelines where schema evolution is critical

- Ingesting data at high throughput where write latency matters

Use Parquet when:

- Running analytical queries on large tables in Spark, Delta Lake, BigQuery, or Athena

- Working with nested data structures (arrays, maps, structs)

- Building any modern Lakehouse (Delta, Iceberg, Hudi all default to Parquet)

Use ORC when:

- Your stack is Hive, Presto, or Trino-heavy

- Maximum compression ratio is a priority (e.g., archival data lakes on HDFS)

- You need bloom filter-level skipping for high-cardinality point lookups

Summary

- Row formats (CSV, JSON, Avro) write fast but read slow for analytics.

- Columnar formats (Parquet, ORC) enable predicate pushdown and projection pushdown. This helps Spark to skip row groups and unused columns at the I/O layer.

- Parquet is the default for Spark and the Lakehouse ecosystem.

- ORC wins on compression ratio and has bloom filter support and is ideal for Hive/Trino stacks.

- Avro is your best friend for Kafka and streaming pipelines. It has appendable, fast writes, schema evolution built in.

- Combine columnar formats + partitioning for multiplicative I/O savings: partition pruning skips folders, predicate pushdown skips row groups within those folders.